Your customized benefits technology platform

When you’re juggling benefits technology, health insurance technology, and an HR platform, confusing and complex processes are inevitable. Create® Technology is a proven, best-in-class platform that brings everything together. It’s all in the same platform, tightly integrated to keep processes moving, members connected, and admin teams productive. When you have the ability to customize everything, you always get the perfect fit.

Take control of the entire member experience

Empower

members

Bring your members closer to your plans with a branded self-service portal where they can enroll, manage membership, and look up providers in moments.

Simplify

admin

Remove the hassle from benefits and payroll administration. Run membership, participation, and eligibility reports, download information and more.

Customize Experiences

We will customize the technology platform to match your rules and processes.

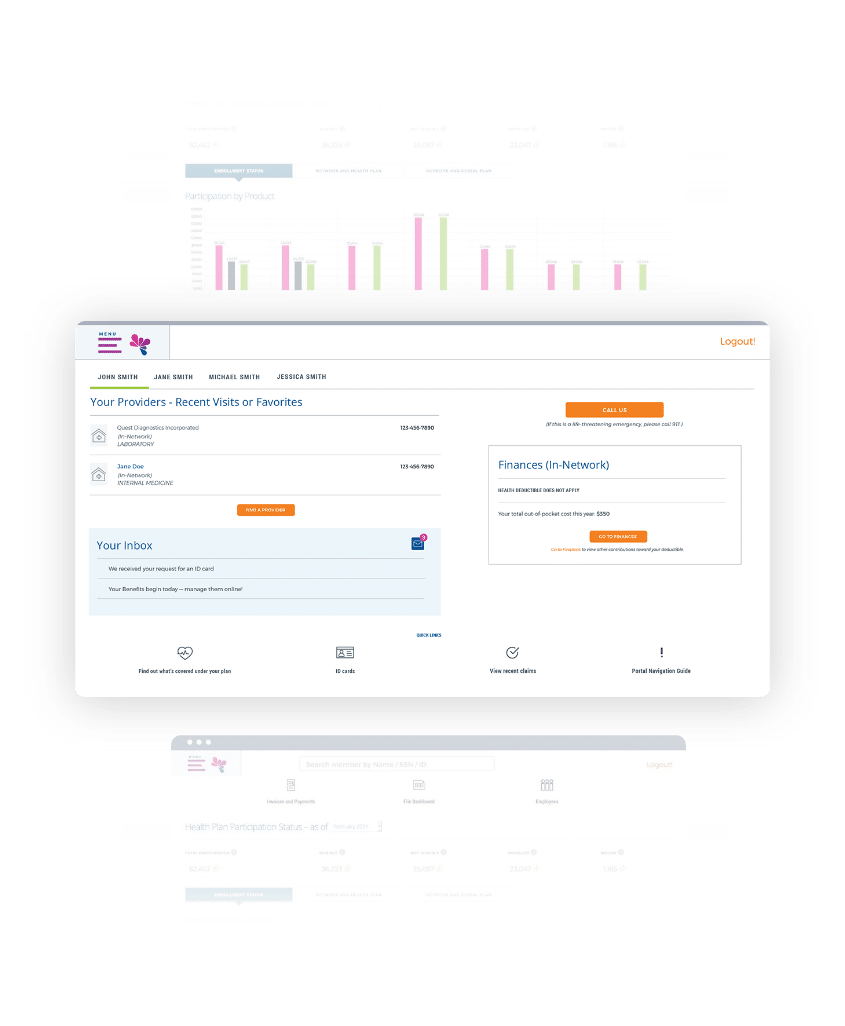

Easy to use. Easier to manage.

Improve your member engagement and streamline your administrative processes.

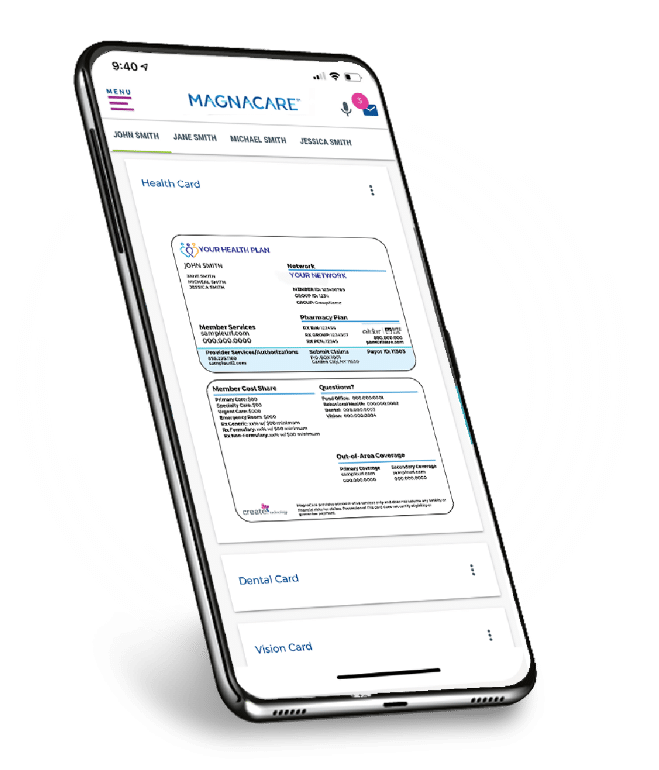

Membership on the move

With our dedicated app for smartphones and tablets, Create® Technology lets your members search providers, manage claims, receive messages, and more — whenever and wherever they want.

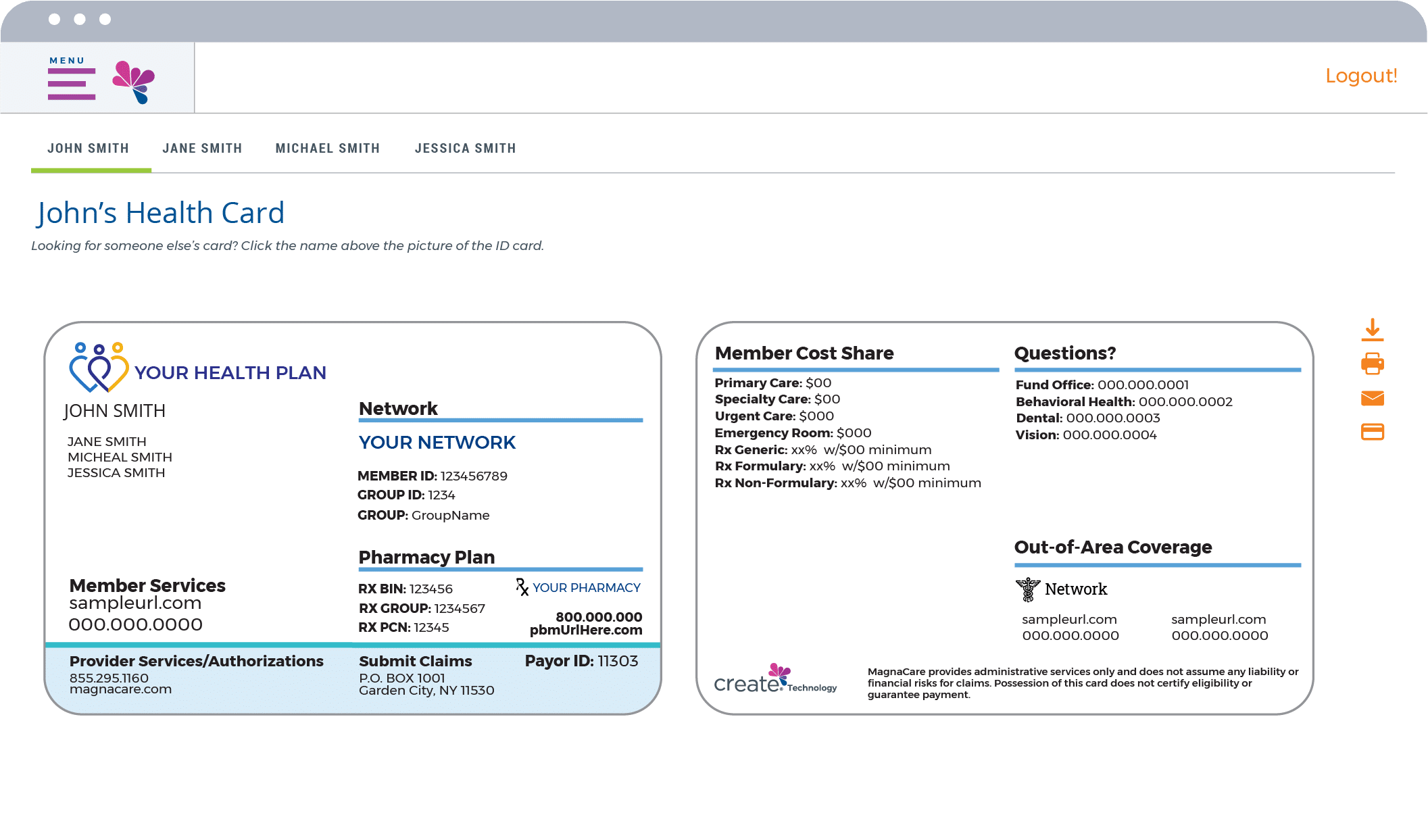

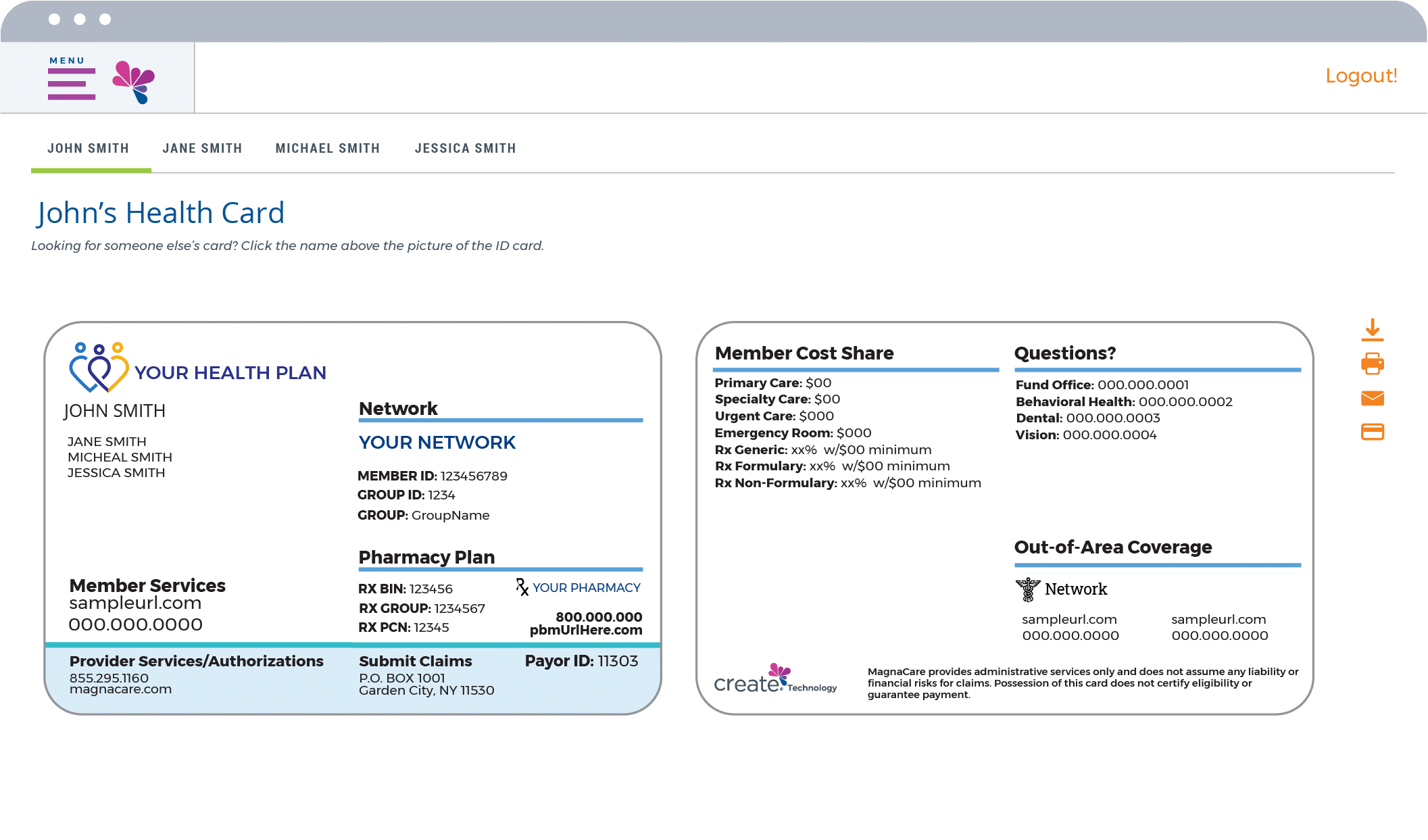

Intuitive Member Portal

Make it easy for your members to choose, use and manage their benefits. Our Member Portal is designed to empower members with flexible self-service across their entire experience. Whether they need to look up coverage, show ID cards, review explanation of benefits, or track their own expenses, it’s all just a few taps away.

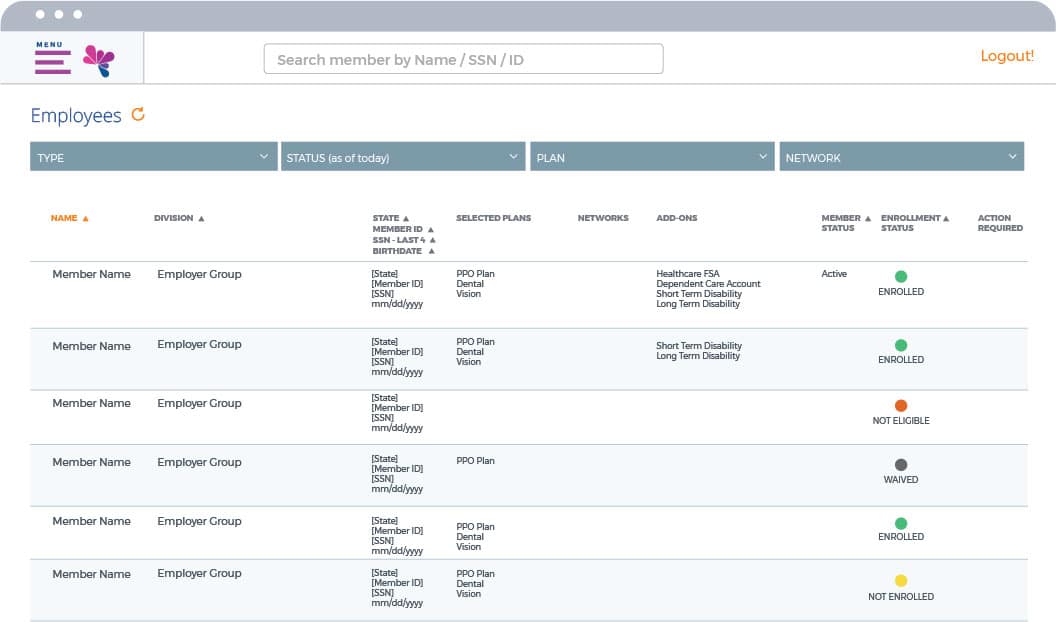

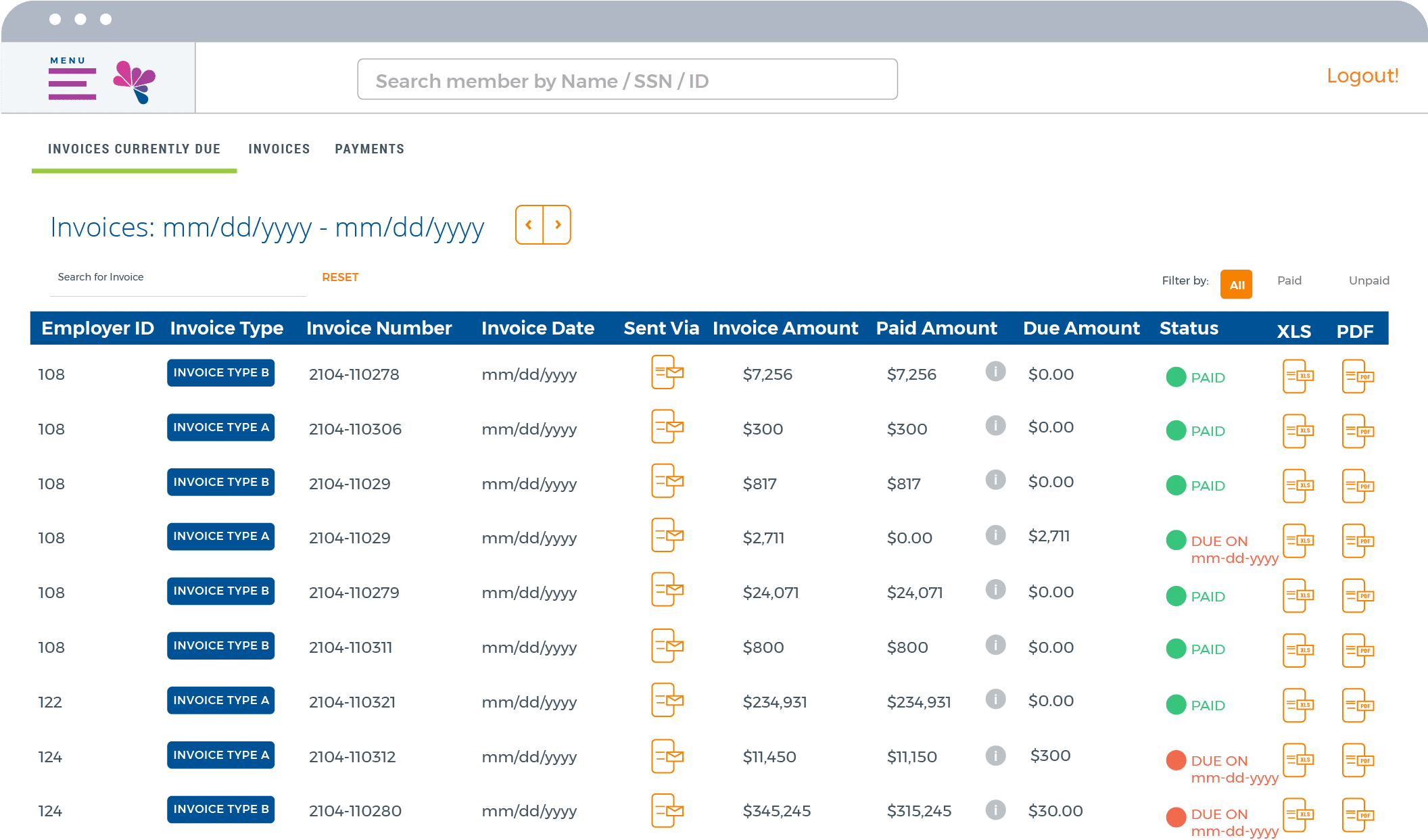

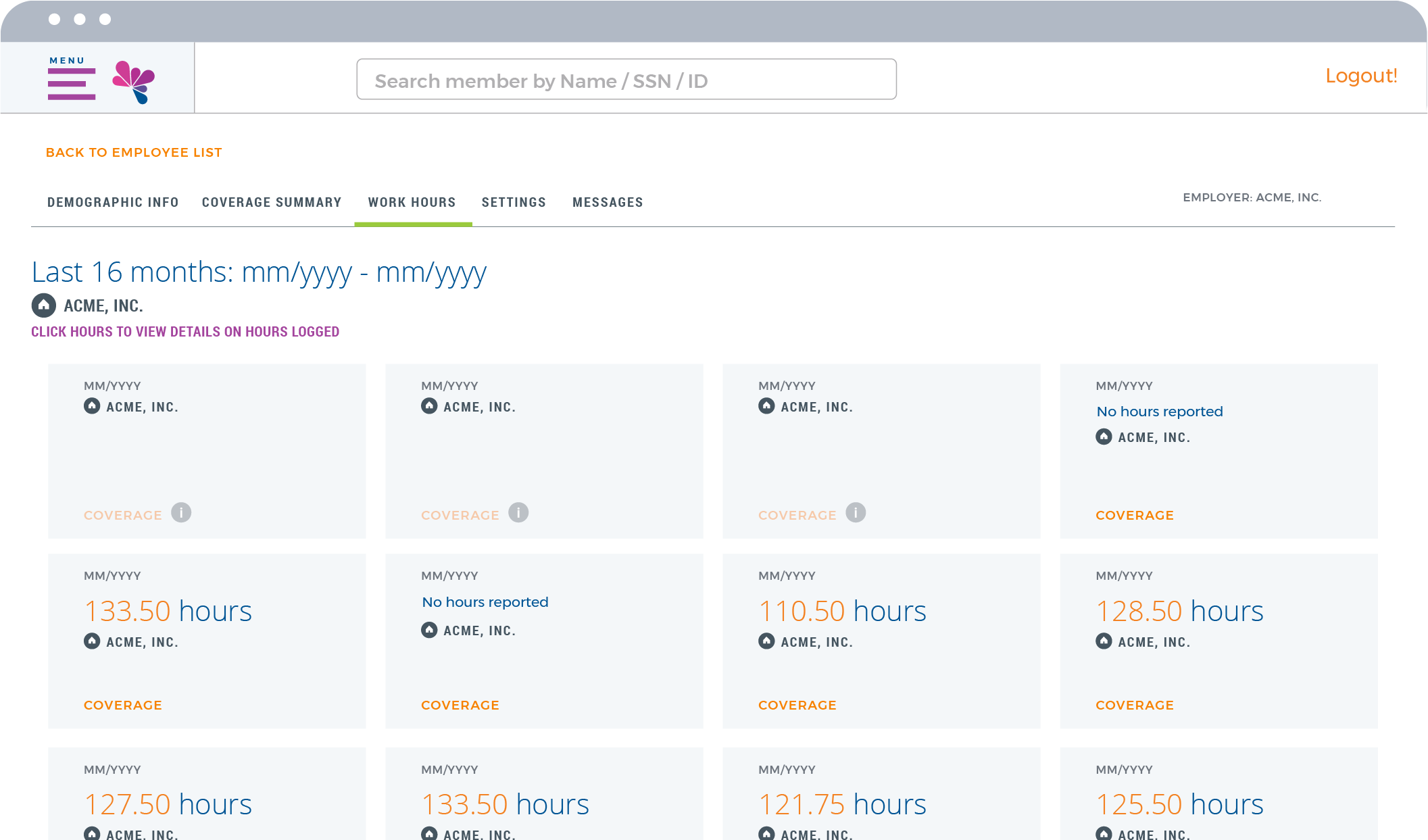

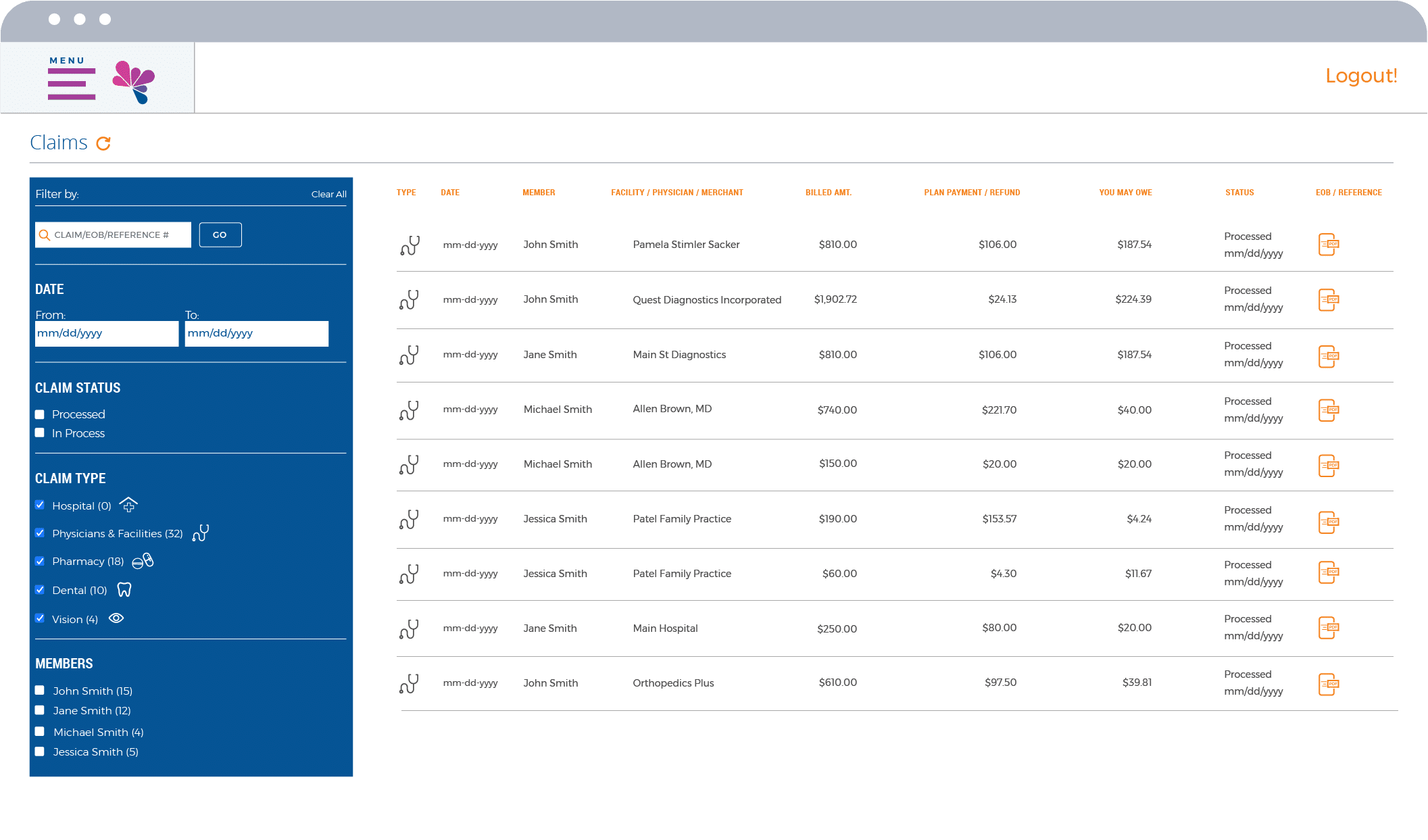

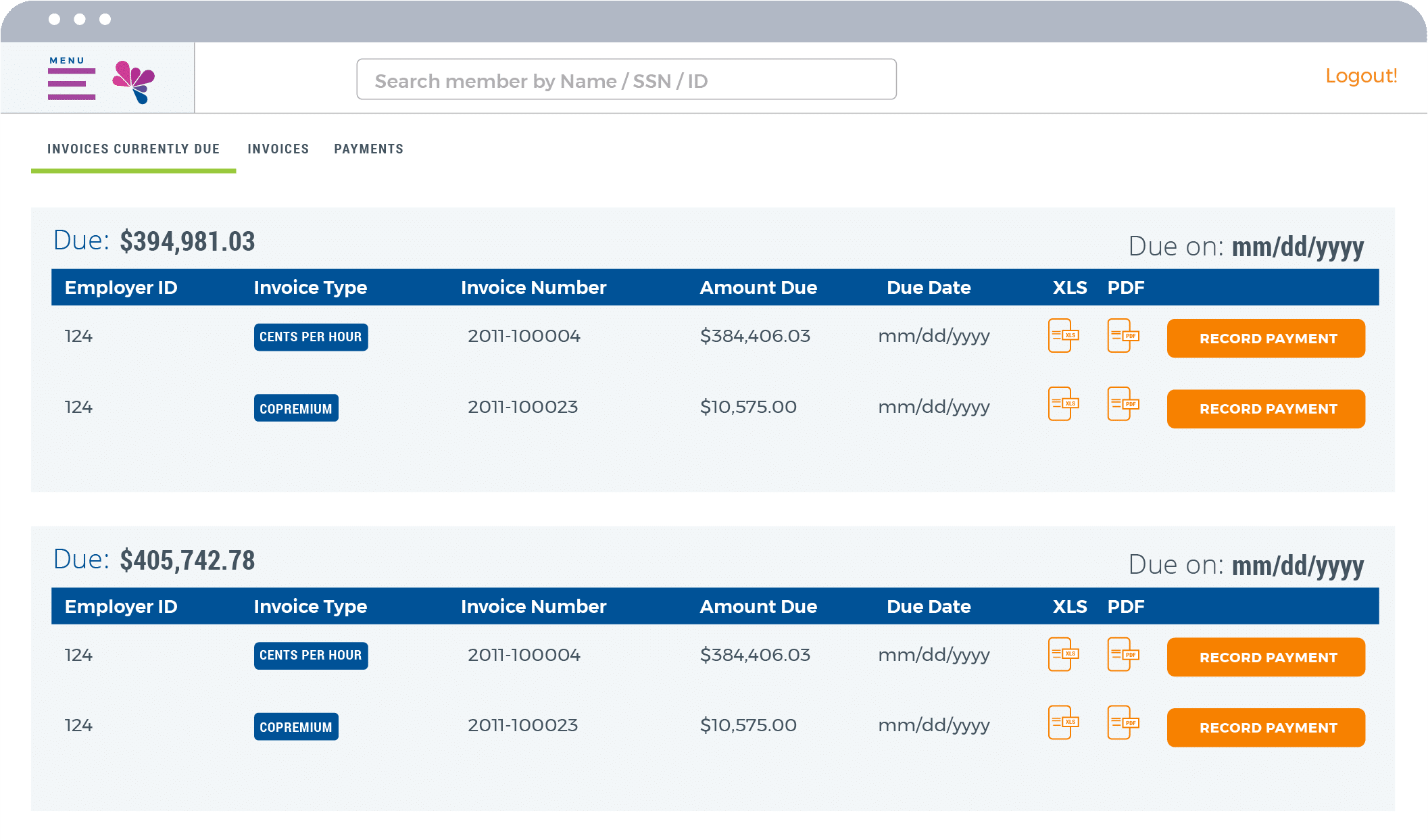

Innovative Employer Portal

For employers, our Employer Portal is an impactful way to simplify administration, achieve compliance, and save money. Checking eligibility? Easy. Tracking payments? Painless. All with ready-made compliance reporting and significant cost savings compared to paper documents.

Digitize your benefits enrollment

Say goodbye to the frustration of missing information and slow post-enrollment processes. Create® Technology guides your members every step of the way while bringing data directly into your systems and tools.

Ready to talk it over? We’re ready too.

Get in touch and get a third-party administration partner you can rely on.

Call 888.799.6465 or fill out the form below

Partner With Us

MagnaCare Blogs

What to Expect from the Minimum Essential Coverage (MEC) Application Process

Finding a healthcare plan for your company isn’t…

Information on Change Healthcare Cybersecurity Incident

As widely reported in the media, Change Healthcare…

One Strong Voice

Explore Laborstrong.live, the premier online platform for Union members, leaders and supporters.